Early Childhood Development: Phonemic Awareness

Phonemic awareness is the ability to recognize, differentiate and manipulate the individual sound units in spoken words. As if the term “sound units” wasn’t pretentious enough, early childhood educators and speech therapists often refer to individual sound units as “phonemes.” Phonemes are more than just syllables. The word “hat” has one syllable, but three phonemes: the /h/ sound, the /a/ sound and the /t/ sound.

Common Notations Regarding Phonemes

Teachers typically use three common practices when discussing letters and their sounds, and I will follow all three practices throughout this section:

- Writing the letter M, for example, to signify the letter M and writing /m/ to signify the sound the letter M makes (“mmmm”).

- Using the phrases “short vowel” and “long vowel.” An example of a “short vowel” would be /a/ in “cat” whereas a “long vowel” would be /a/ in “plate.”

- Using the phrases “hard consonant” and “soft consonant.” The letters C, G, and S all have “hard” and “soft” sounds. An example of a “hard C” would be /c/ in “cat” whereas a “soft C” would be /c/ in “cent.” An example of a “hard G” would be /g/ in “game” whereas a “soft G” would be /g/ in “gym.” An example of a “hard S” would be /s/ in “prize” whereas a “soft S” would be /s/ in “sat.”

Stages of Phonemic Awareness Development

Phonemic awareness starts with babies hearing and repeating consonant sounds like “bah bah” or “dah dah” and progresses to fluent speaking. Phonemic awareness skills are acquired over a span of several years and develop in sequence.

- Recognizing individual words in a sentence.

- Recognizing individual sounds in a word.

- Recognizing rhyming words.

- Identifying syllables (word parts).

- Recognizing or matching identical consonant sounds at the beginning of words. For example, matching the /b/ at the beginning of “balloon” and “bike.” This often happens by age four or five.

- Recognizing or matching identical consonant sounds at the end of words. For example, matching the /t/ at the end of “jacket” and “bat.” This skill is normally developed by age five or six.

- Recognizing or matching identical consonant sounds in the middle of words. For example, matching the hard /g/ in the middle of “wagon” and “digger.” This skill generally develops by age six or seven.

- Recognizing or matching identical vowel sounds in the middle of words. This includes matching the short /e/ in the middle of “bed” and “hem.” This skill normally develops by age six or seven.

Importance of Phonemic Awareness

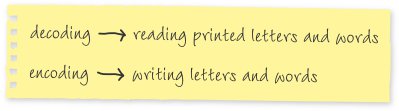

The relationship between phonemes and letters is the basis for reading and writing. Of course, we educators have fancy terms for these processes also:

Relationship Between Phonemic Awareness And Reading

Children first start reading by developing a sight word vocabulary. A sight word vocabulary is a collection of words that your child is able to “read” simply by looking at the word and without having to sound it out letter by letter. Children typically begin creating a sight word vocabulary as early as age 3 and the number of words in that vocabulary grows exponentially as the child gets older.

As your child begins a formal reading program (normally in kindergarten or first grade), he will naturally encounter numerous words outside of his sight word vocabulary. When this happens, he will need to “sound out” the word by saying aloud (or thinking aloud in his own head) the sound each letter makes and coupling all the sounds together to form the word.

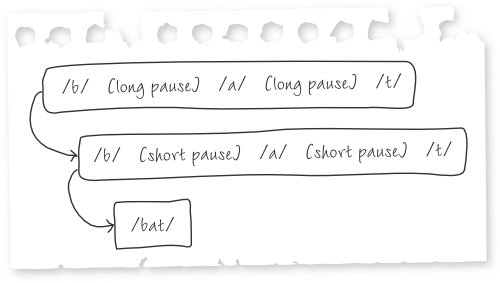

For example, consider the word “BAT.” If this word is outside of your child’s sight word vocabulary, he will need to sound out each letter. First, he must see the letter B and identify the /b/ sound. Then he must see the letter A and identify the short /a/ sound. Finally, he must see the letter T and identify the /t/ sound. It is common for young children to say aloud each distinct sound they identified and repeat those sounds until they can decode the word. That process typically looks like this:

Beyond reading the single word “bat,” a child must also be able to carry the knowledge of the sounds made by each and apply it to future words. For example, a child must remember the sound /ba/ made by the B and A and apply that knowledge to words such as “bad” or “bag.”

Relationship Between Phonemic Awareness And Writing

When writing, a child must be able to accurately isolate and identify the sounds in the word he wishes to write. After identifying the sounds in the word, he needs to write the appropriate letter for each sound. For example, a child wishing to write the word “hat” must first identify the distinct sounds in the word: /h/, /a/, and /t/. Then, he must be able to recall the letters that correspond with the sounds he has already identified: H, A, and T.

Once a child identifies the letters representing the sounds in the word he wishes to write, he can begin the process of writing the word. This can include a child writing the letters himself on the page or, before he is ready to write himself, dictating to a teacher or adult the letters to write. In either case, this very early writing is called “phonetic writing” or, perhaps more aptly, “inventive spelling.”

Inventive Spelling

Inventive spelling occurs when a child applies letters to the sounds he deciphers in a word and uses those letters to represent the whole word. The wonderful thing about inventive spelling is that is allows a child to express themselves in writing long before he is able to correctly spell all the words he wishes to write.

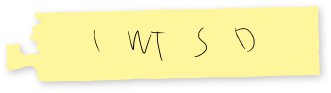

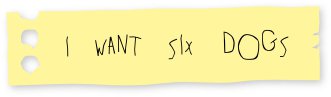

An example of inventive spelling might look something like this:

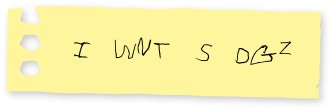

With time, as the child’s phonemic awareness skills further develop, he will be able to hear and distinguish even more sounds in the sentence he is trying to write. When that happens, the same sentence may turn into:

With even more time, the child will be able to hear and distinguish all the sounds and letters in the sentence. When that happens, the sentence will turn into:

Interestingly enough, inventive spelling is making a comeback among teenagers and adults as text messaging grows in popularity. Consider the text, “hv to go bcuz im late.” The word “because,” when spoken aloud, has only a few dominant letter sounds: /b/ /c/ and /z/. As a shortcut, we default to writing “bcuz” since those four letters, when read in order, mirror the same sounds in the full-length word. Just as a child learning to write defaults to inventive spelling as the most basic way to communicate an idea, so does a teenage or hurried adult with a text message.

Tips for Accelerating Your Child’s Phonemic Awareness Development

The first step in developing critical phonemic awareness skills is to ensure your child is aware of words. Start with simple activities such as having your child clap once for each word you say in a sentence to help solidify this understanding. Then progress to having your child clap once on each syllable as you say a word aloud.

Once your child is comfortable identifying words and syllables he is ready to begin honing more advanced phonemic awareness skills. The most effective way to accelerate your child’s phonemic awareness development is to engage your child in activities where he must identify specific sounds. For example, encourage your child to walk around the house on a “treasure hunt” and collect items that begin with the same initial consonant sound.

To begin, select a consonant sound that your child is easily able to say and hear, such as /b/ or /d/. Have your child walk around the house and either collect items with the proper sound, or just call out the name of the item when he sees it. Challenge him to collect a certain number of items, such as five or ten, before moving on to the next sound. This activity forces your child to say aloud (or in his head) the name of each household items he encounters to see if the initial sound “matches” the sound you have proposed.

To help highlight consonant sounds in words, you can explain to your child how you move your mouth to make a particular sound and suggest that he watch your mouth as you say the words. For example, when teaching my son the “th” sound, I always said, “See how my tongue goes past my lips and my teeth touch down on it a little?” That way, as he formed the sound in his own mouth, he could practice pushing his tongue past his lips and then closing his mouth a little so his teeth touched his tongue.

Knowledge of all 26 letters and their many accompanying sounds is an advanced skill and is not one that your child is expected to have when he begins preschool. As a result, most parents should focus on helping their children simply develop an ear for sounds, as opposed to formally introducing their child to each letter and the corresponding sounds.

If your child is showing signs of being ready to learn the sound(s) each letter makes, please review my Tips for Introducing the 26 Letters and Their Sounds.

Learn More About What Will Be Expected of Your Child in School

When children begin preschool, they are expected to begin recognizing individual sounds in words, count words in a spoken sentence, and identify rhyming words. As a child progresses through preschool and kindergarten, he will be given focused opportunities to listen to spoken words and he will be encouraged to isolate and identify the sounds he is hearing. By the end of kindergarten, a child should be able to identify each discrete sound in spoken words, including sounds at the beginning, end, and middle of words. Kindergarten-aged children should also be able to match those sounds to the correct letter, begin writing through inventive spelling, and play word games such as rhyming and creating compound words.

Beginning of Preschool

When children start preschool, they are expected to recognize individual sounds in a single word and repeat those sounds. For example, a child should be able to suggest a word that starts with the /b/ sound. Children will also be expected to understand the concept of rhyming and should be able to identify when two words rhyme. (Later in the year, children will asked to complete the more complicated task of suggesting rhyming words.)

Children are expected to identify distinct words in a spoken sentence and count the number of words as a sentence is said aloud.

In many preschools, teachers may introduce the sound each letter makes. If this is part of your child’s preschool curriculum, your child is expected to accurately hear each sound the teacher makes when introducing a letter and repeat the sound properly. Children will be expected to remember what sounds each letter makes.

Beginning of Kindergarten

At the start of kindergarten, children are expected to be comfortable with the first five stages of phonemic awareness development. This means a child is expected to (1) recognize sounds in individual words, (2) count words in a sentence, (3) recognize words that rhyme, (4) count syllables in words, and (5) identify the beginning consonant in each word.

In many cases (and based on the school curriculum), children are expected to attempt inventive spelling to communicate their ideas through writing. Children should be able to consistently identify the first letter or beginning consonant of each word they are trying to communicate, as well as any ending consonant or strong vowel sounds. As a general rule, a kindergarten child’s inventive spelling should be advanced enough that an adult could look at the letters written by the child and, by sounding out the letters written, guess the intended words in the sentence. At this point in the year, children are not expected to spell words correctly. As such, the letters C and K or Z and S, for example, will be considered by children largely interchangeable due to their similar sounds. This understanding is absolutely expected and permitted.